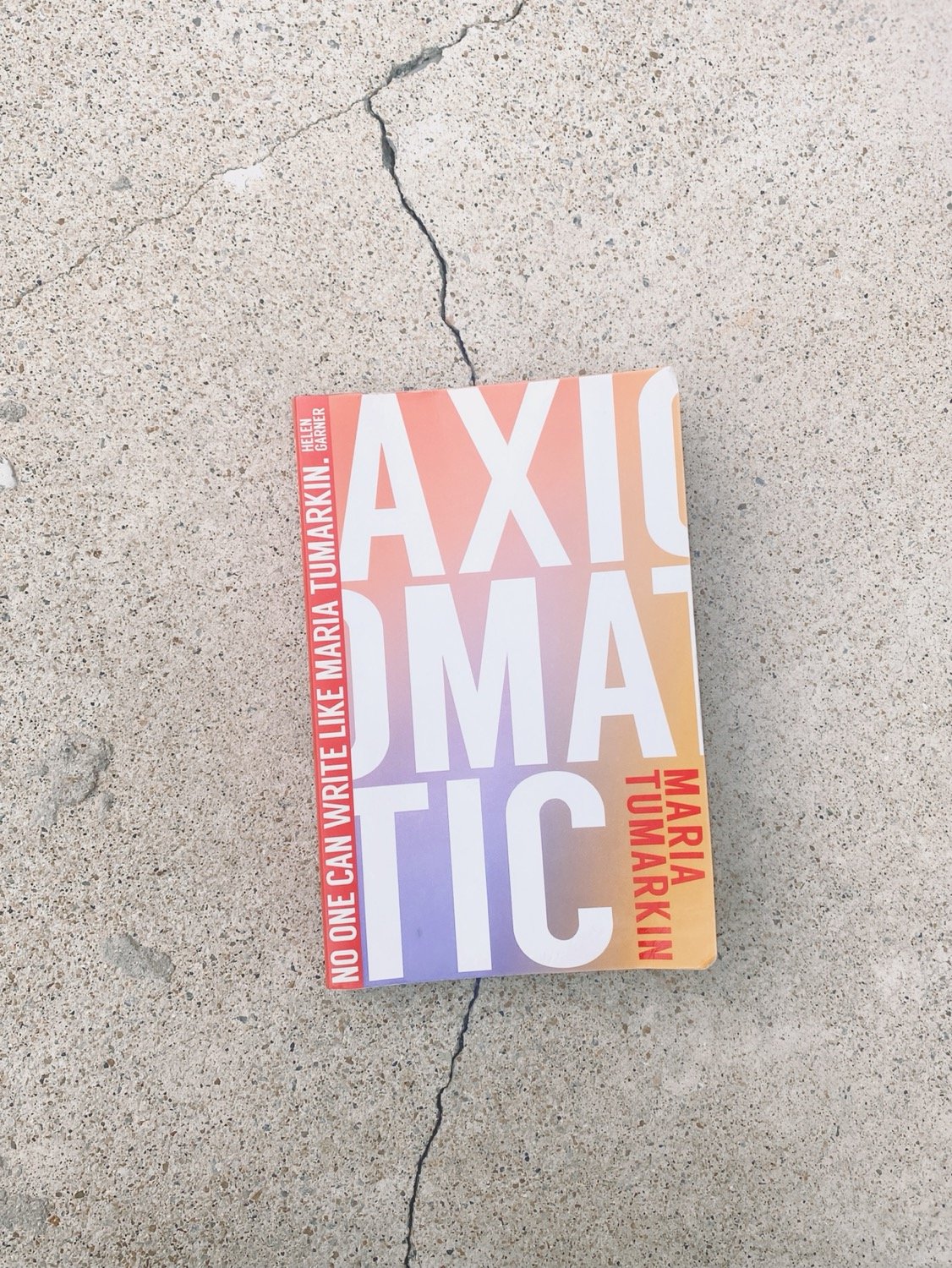

On a line, inside a circle

on Axiomatic by Maria Tumarkin

I call my emotional bouts “cry sessions”. They come regularly, often suddenly. Washing over me (It doesn’t actually feel like being washed, it feels as if I’m being swallowed by a tar pit): a wave of memory, insecurity. Other times, paranoia. In the past year it has been grief – my own, and the extension of others’. Its smallest form is grief over uncrossable distance; its largest and cruelest is death in multiples. I wish I could still point to the pandemic. I wish, almost two years on, it’s still easy to fault an illness that could never right its wrongs. Because naming an offender makes me wish for justice, but there is no justice in untimely death, not really. No, I don’t want to hear about God’s good time. His time does not permit resurrection beyond anecdotes. “Time as a straight line is a monstrosity,” Maria Tumarkin writes. Time kept growing and expanding. My cry sessions couldn’t help but do the same.

I realise now that I’m not just talking about this virus, I’m thinking of some other illness, an illness Susan Sontag wrote about in length. I must also inform that this is more about the aftermath than it is about the illness, and that this is written with great hesitancy because the grief isn’t mine. I felt it indirectly, really, because it was a loved one’s someone, and though she was a great someone to me too my grief was much smaller. Back in April after reading Zadie Smith’s Intimations I asked how you may grieve a grief that isn’t yours. The answer is poorly, I think, and slowly, inefficiently. My greatest duty was to the owner of that grief, and I said all things you would say to someone who’s deeply grieving, and more. Not to the greatest effect, but that’s another matter. Something only time can take care of.

I began by saying she isn’t really gone, although that’s not true. To my friend her mother is gone in every sense of the word, it is impossible to see otherwise. So I stopped saying that she’s not gone, because I understood that existing in spirit is often inconsequential. For months I told her, I can’t go home, but I am with you always. In spirit. And in that way I was always limited, because spirit unless manifested is inconsequential. That’s the reason why when we tell stories of ghosts we speak of sightings, a cold breeze over our neck, or a whisper just below our frequency. That’s why we call it a presence. But me? My absence was always bigger.

Next I told her to cry, because it seemed that everyone was telling her to be strong, to be patient. I thought if she built forts instead of bridges it will only compound her loneliness. I also told her to cry because that’s what I was doing. Over her mother’s death or over my incapacities as a friend I am unsure. But I cried everywhere. On my commute home, in a morning meeting, quietly turning off my camera. I sobbed into my partner’s shoulder, I don’t think I will ever forgive myself. I was supposed to be comforting her and yet I needed comforting myself, it was pathetic. I was asking her how she was every week or so, but it took me almost two months to see her on facetime. To apologise. This was equally pathetic. When we finally did speak on facetime it became a joint cry session (co-weeping, I wrote in April). I realised that she was overcome knowing that she was not alone in her loss, that her mother’s kindness extended beyond her family; existing in multiples. Even when the life she knows is gone there is a fraction of her I will always hold with me. That day I gave it to her she cried some more. Not because her mother lost a life but because she lived a life.

The next thing I told her was to stay behind, just for a little. She doesn’t know how to go on, she said, how can people move on with their lives? How can they tell me to do the same? She said, my universe is now a gaping hole, anywhere I go I’m bound to fall in. So I told her to not move on. Take your time, recall every inch of memory you have. Go through the photos, make a scrapbook. Last ditch effort at immortality. Maria Tumarkin writes: “Nothing is more human than the experience of feeling trapped. And everything is a trap, your past, family … that feeling that pretty much everyone else is galloping gaily ahead while you are crawling backwards like a lobster or a lopsided baby.” I think that’s what she felt like. Like she was crawling backwards while the world goes on without her, and without her mother. But I can’t seem to find anything wrong with it, maybe because I wasn’t the one feeling the loneliness of it all. But I think life, the everyday, the dull and repetitive will bring her forward regardless. She would have to hop on the travelator, whether she is ready or not, because there are tasks to fulfil and lives to care for. She doesn’t have to make that excruciating effort to move on. Time will bring her there. I thought she had every right to stay behind, to remain somewhat paralysed. A safety bubble to keep her memories from leaking. I am tempted at times to tell her that it is time to move on, because I know this bubble also protects her grief. But memory and grief supports each other’s existence, and so I stand by to make sure that when the bubble deflate it will do so slowly. Strangely in April I thought grief is something of a river: “sorrow leaks, and I can’t seal the gash. I can only let it flood, and knock on the borders of my circle: hello, how are you, stay afloat, you are not alone.” Metaphors aside – my point stands.

Time as a straight line is a monstrosity,” Maria Tumarkin writes, but what’s even more monstrous is that time remains a straight line while grief runs in circles. You don’t know where it ends and where it begins. Or rather, the beginning bleeds into the circle and disappears. The end and the beginning is unclear when the grief is yours, even more so when it is not. I am limited, at times, inconsequential. There is little I can do that cannot be done by the average bystander. But it is sufficient, for the time being, as long as time doesn’t wander about a sharp turn. “Time is what makes everything OK,” Maria Tumarkin says, and as long as it is bearable we choose to believe it. The alternative is unthinkable.

Stay afloat, please, my friend – you are not alone.